Transforming Post-Merger Operating Culture

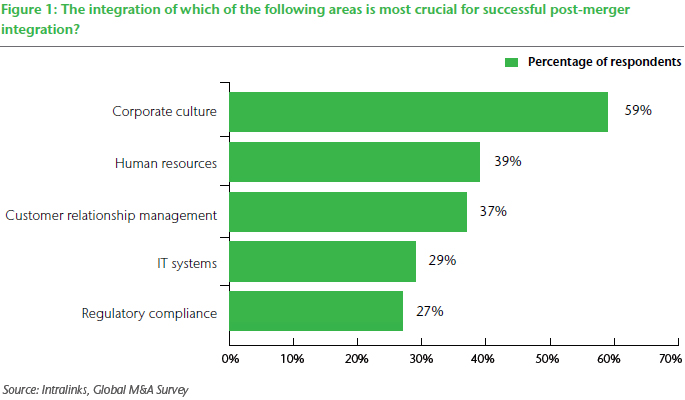

We regularly hear from our strategic stakeholders, i.e., CEOs, Heads of Corporate Development and CHROs, that their top concern in a merger or joint venture (JV) is how corporate culture might derail the successful achievement of post-merger goals. Numerous studies, including ones conducted by Aon Hewitt, bear that out.

While we all appreciate the importance and complexity of culture, the real question that emerges is twofold:

- How do we define current and future culture, and on what parameters?

- How do we successfully execute this shift without disrupting business, customers, and risking post-merger deal goals?

Interestingly, we have found that when we pose these questions to our clients, we get very different answers, or worse still, no clear answers. In this article, we attempt to provide both a framework and an approach to address these two critical questions that every CEO is (or should be) asking as he/she considers a transaction.

So how do we go about defining ‘culture’? First, it’s important to step back and understand, what is culture in the context of an organization and a transaction.

Culture has two aspects. One is the familiar idea of national culture. But the more critical aspect is the ‘operating’ or ‘corporate culture’. Aon Hewitt describes operating culture as an organization’s ‘operating environment’, or more simply as ‘how work gets done’. It’s the operating culture that is key and constitutes the make or break element in transactions. Very often, we find that firms get too caught up in national culture and its implications. Make no mistake, national cultural differences are indeed crucial and need to be addressed. But the more fundamental piece is the operating culture. Mergers or JVs fail essentially because of issues that an operating culture mismatch creates.

How does operating culture manifest itself? The following are actual examples of its manifestation:

- Core aspects of a firm’s strategy – Is the firm’s strategy to be innovative vs. process and replicating innovation? In a recent technology global merger between a global Asia major and a US technology firm, the intent of the deal was to utilize inherent IP of the target to drive innovation in the combined entity to leapfrog into the mobile space. The firms’ operating model – a technology & telecom sector merger in Asia involving a large acquisition that resulted in doubling the acquirer’s workforce – the focus was on driving process excellence gains in the acquired operation and this was a ‘non-negotiable’ cultural element in the goforward culture.

- Firm’s value proposition to its customers – There is always a dilemma on how to balance customer intimacy and customization vs. a standardized approach.

- How decisions are made – Are decisions taken in a centralized or delegated manner? Are the decisions by one leader, a committee, or by consensus? In a chemical-sector Asian client targeting western acquisitions, we found that there was a flashpoint between decentralized, individual-led decisions vs. now everything has to go through Asia Global HQ.

- How information flows – Is information tightly controlled or shared in an ad hoc manner vs. shared in an open and structured manner? In the case of a commodities-sector client, we found that information flow in the smaller, stand-alone acquired entities was unstructured and dependent on the principal/top leader. This precluded post-deal monitoring and governance, and failure to achieve the deal goals.

So the cultural question is often structural and hard-coded in the way the firm does business, and is not the soft, amorphous view that was often presented. Ironically, a fact that many leaders miss is that the national culture differences relevant to business, can also be broken down into these operating culture elements.

Let’s examine a few factors that are key to appreciating this operating culture riddle.

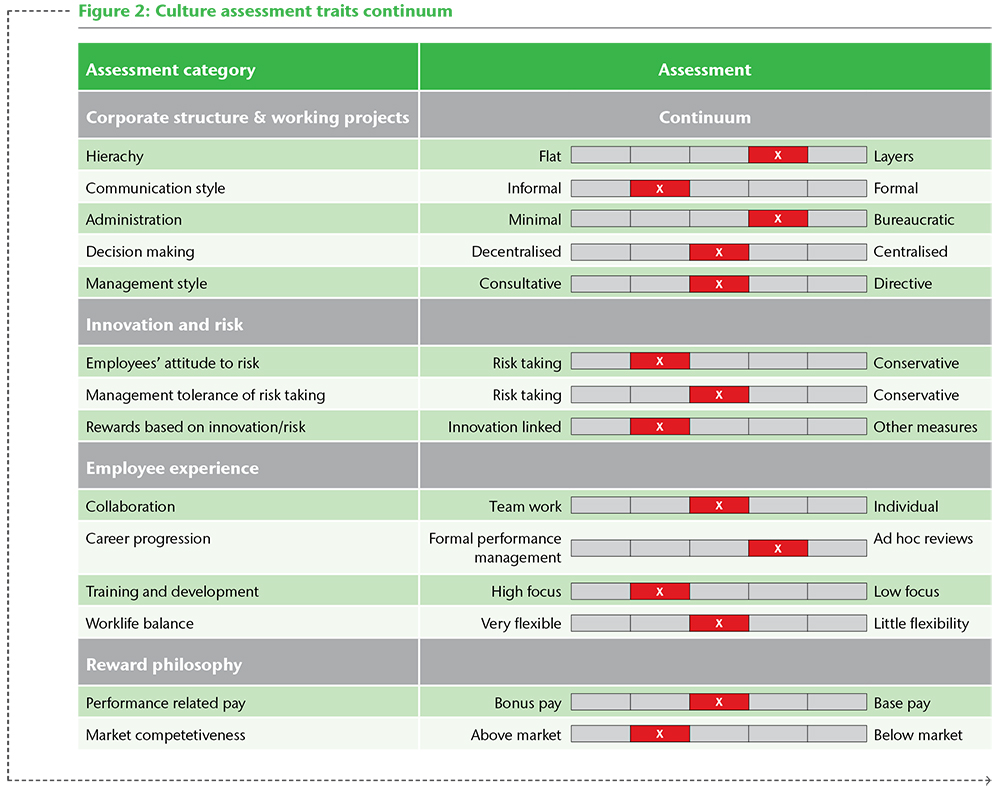

- First, it’s critical to recognize that there is no right or wrong answer on these cultural elements. These are continuums and you need to land on the desired peg of this continuum.

- Second, the culture change is part of the ‘journey’, not a destination. In fact, the desired positioning on culture elements can itself move. The desired end state on each element can change due to multiple factors that a firm encounters, such as undertaking an integration, strategic shifts, change from a minority to majority JV stake, business environment changes, external shocks, changes in control, a leadership change, and so on.

- Third, while most culture elements are a continuum, there are always some non-negotiables with a clear peg – adherence to compliance, result & performance orientation, process excellence, etc.

In every merger, JV or strategic partnership, these points of difference will cause friction and result in flashpoints. ‘Flashpoints’ are points that cause a clash, disruptive disagreements. They pose a risk in the smooth functioning of the post-deal operations.

To bring these concepts to life, let’s look at a few real client examples of these operating culture flashpoints.

- Focus: An Asian client that had acquired a private equity-backed firm in the US in the industrial/chemical space faced an inordinate focus being placed on cost management, characterized by a short-term, firefighting attitude rather than growth, innovation, or a futureoriented culture. It thus ran the risk of its entire deal model and goals being thrown in jeopardy.

- Centralized approach: A western commodity major that has done multiple JVs with majority or equal stakes in Asia has repeatedly faced delays or failures in realizing the strategic goals. They found out that decision-making and information flow in the JV partner was too centralized at the top, seriously impacting speed of execution and day-to-day operations. This, in turn, made it very challenging to execute the time-bound strategy that the JV envisaged.

- Performance goals: A US-based industrial major, after acquiring an Indian local firm, found a fundamental mismatch in performance orientation and result focus. To the extent that there was no process, quality or efficiency goals for any function, the ‘performance bonus’ was not linked to performance or goals.

In addition, all decision-making, from incidental invoice approval to plant operational decisions, up to technology or capital budgeting decisions, was completely centralized. This was contrary to their deal assumptions of being able to execute rapid operational improvements, expansion, and product enhancements. - Misalignment: A global financial major was acquiring a large local player in one of the large Asian economies. Their plan was to shift the strategy of the integrated entity to a customer segment focus, rather than a product focus. They soon realized that the organization design, processes, and product design were all completely misaligned to this new strategic reality. The client quickly realized that if they did not correct this through a massive and radical intervention, the deal rationale would very quickly evaporate.

- Ambiguity in focus: A global telecom major running managed services deals in Asia realized that ambiguity on process efficiency/improvement focus was a very slippery slope, which caused deals to become unprofitable and fail very quickly.

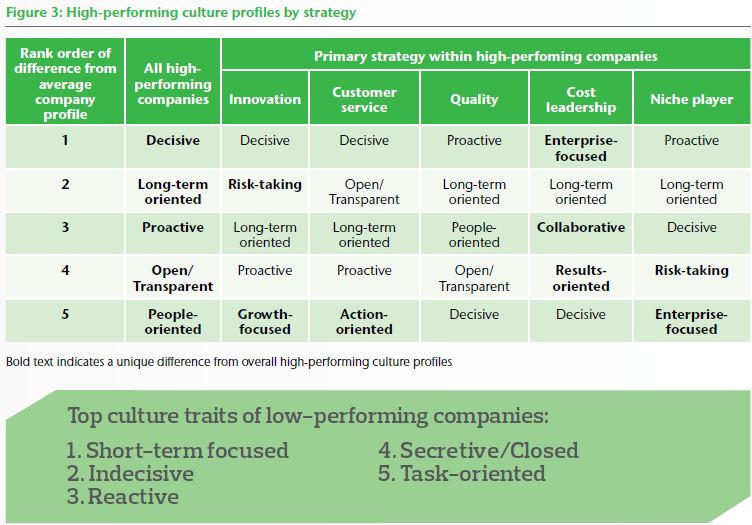

Bold text indicates a unique difference from overall high-performing culture profiles

Top culture traits of low-performing companies:

- Short-term focused

- Indecisive

- Reactive

- Secretive/Closed

- Task-oriented

The contours of culture

The question on a leader’s mind is whether the issues highlighted above can be avoided, or at least managed proactively? The key is to understand ‘the contours of the two operational cultural elements’, or put another way, the root cause of these flashpoints.

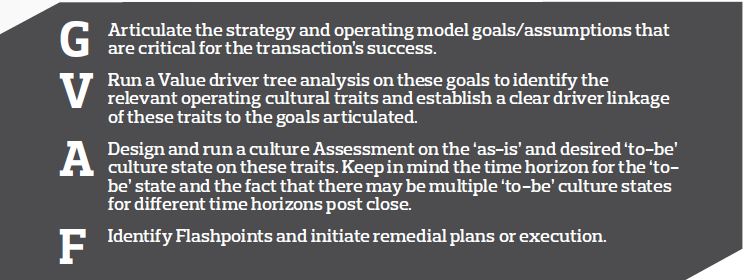

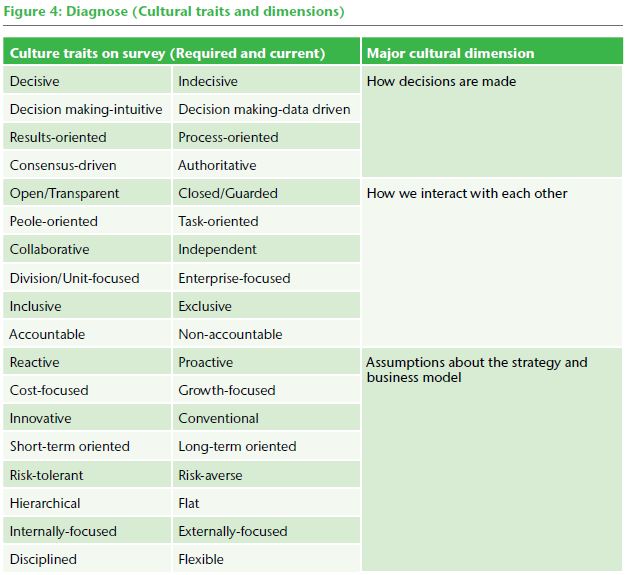

Let’s examine Aon Hewitt’s GVAF framework, which helps us understand and address this operating culture misalignment:

Another key factor for successful firms is that they undertake the above process between announcement and close. This is followed by detailed execution post close, as per the plan.

The shift strategy

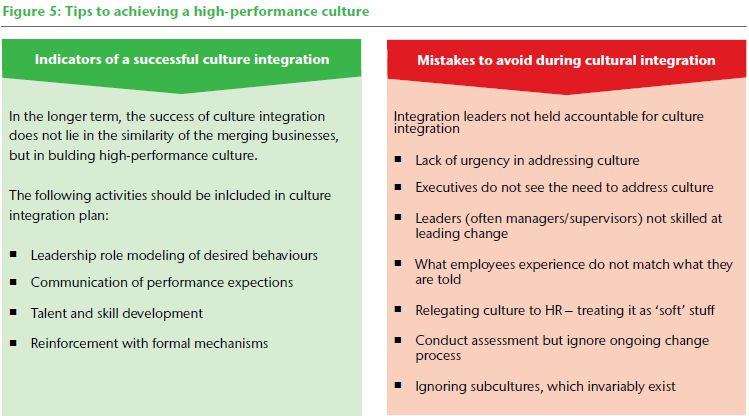

It’s important to appreciate that a shift is possible only when you have clarity on what the flashpoints are, how they are linked to your deal goals, where you need to focus, the execution plan/dos & don’ts (see Figure 5 on the following page), and finally, how the outcome of culture alignment is ‘measured’.

Let’s now examine some of the mechanisms to enforce this culture shift:

- Desired culture has to be defined in four to five key traits and clearly linked to strategic goals.

- Implant the desired-goal culture definition and link it with the Executive Leadership team, and then cascade it down to the lowest level through functional leaders and managers.

- Embed desired ‘to-be’ culture traits in process, go-to-market approaches, business & HR policy and behaviours.

- Use communication and change agents to propagate ‘viral change’.

Of the above, ‘viral change propagation’ of culture shift is an innovative adaptation from the new product (or concept) adoption strategy, followed by organizations to drive product adoption with customers. As in new product adoption, if executed well, it can have a huge impact on the success of the initiative and the actual degree of the culture shift. It utilizes the concept of multiple generations of change champions, infection rate goal, and positive/negative multipliers.

In conclusion it’s absolutely possible to ensure culture shifts, as we have seen from many of the successful culture change examples. However, it requires very structured and deliberate efforts to understand, plan, and execute ‘maniacally’.

Authors:

Sharad Vishvanath

SVP & Partner, Regional MD Asia Pacific, Middle East & Africa

Aon Strategic Advisors & Transaction Solutions

[email protected]

Get in touch